In a judgment handed down on 30 September 2020, PLK & Ors (Court of Protection : Costs) [2020] EWHC B28, Master Whalan has considered the concerns the method of assessment of the hourly rates claimed by Deputies. The SCCO consolidated the assessments in four cases that chosen to represent the costs claimed by Deputies in different parts of England, in the management of the affairs of protected parties who had sustained significant brain or birth injuries. The central submission of the deputies was that the court’s current approach, which, broadly speaking, relied on the application of the Guidelines Hourly Rates (‘GHR’) approved by the Costs Committee of the Civil Justice Council was, by 2020, incorrect and unjust. Instead, they submitted, the assessment of COP work should be predicated on a more flexible exercise of the discretion conferred by CPR 44.3(3), whereby the GHR were utilised as merely a ‘starting point’ and not a ‘starting and end point’.

Master Whalan did not accept the primary argument of the applicants that COP firms had experienced

29. […] ‘a significant increase in hard and soft overheads’ (SA, 45). The evidence, both in respect of time and expenditure, is inconsistent and, in my view, incomplete. Nor am I persuaded by the submission made in the oral hearing that ‘it is clear that no other area of practice requires such a level of unrecoverable time’. So far as the datum is consistent and stable – and, as noted, the most reliable figures are probably those produced by Clarion – it suggests a comparatively modest incidence of time and expenditure. However reliable the figures produced may be, they do not, in my view, demonstrate that the burden is one that is exclusive to COP work or that it is atypically high in comparison with that experienced by practitioners in comparable areas of practice. Fee earners in personal injury, medical and professional negligence, for example, incur invariably time and expense that is irrecoverable, in marketing, accessing cases that are not proceeded with or, indeed, pursued and lost. These are burdens which do not apply to Deputy’s sources of work (on a case by case basis) which is often consistent and predictable over many years.

However:

Three preliminary observations then inform my initial approach to the applicants’ secondary argument. First, it should be emphasised from the outset that this court has no power to review or amend the GHR, either formally or informally, as this role is the exclusive preserve of the Civil Justice Council. This reality is recognised properly by Mr Wilcock in his written and oral submissions. Secondly, while the court has received submissions concerning the application of an inflationary uplift when applying the GHR, this is not just a ‘blunt tool’, but an approach which endorses the application of a practise which has been rejected explicitly since 2014, from which time the emphasis has been on a ‘comprehensive, evidence based review’. Thirdly, however, it must be acknowledged that the GHR cannot be applied fairly as an index of reasonable remuneration unless these rates are subject to some form of periodic, upwards review. O’Farrell J. in Ohpen (ibid) observed that it ‘is unsatisfactory that the guidelines are based on rates fixed in 2010’ as these ‘are not helpful in determining reasonable rates in 2019’. These observations were made in the context of an assessment of London City solicitor rates in an assessment where the court was not bound by the GHR. It seems clear to me that the failure to review the GHR since 2010 constitutes an omission which is not simply regrettable but seriously problematic where the GHR form the ‘going rates’ applied on assessment. I do not merely express some empathy for Deputies engaged in COP work, I recognise also the force in the submission that the failure to review the GHR since 2010 threatens the viability of work that is fundamental to the operation of the COP and the court system generally.

Against this backdrop, Master Whalan concluded that

35. I am satisfied that in 2020 the GHR cannot be applied reasonably or equitably without some form of monetary uplift that recognises the erosive effect of inflation and, no doubt, other commercial pressures since the last formal review in 2010. I am conscious equally of the fact that I have no power to review or amend the GHR. Accordingly my finding and, in turn, my direction to Costs Officers conducting COP assessments is that they should exercise some broad, pragmatic flexibility when applying the 2010 GHR to the hourly rates claimed. If the hourly rates claimed fall within approximately 120% of the 2010 GHR, then they should be regarded as being prima facie reasonable. Rates claimed above this level will be correspondingly unreasonable. To assist with the practical conduct of COP assessments, I produce a table below which demonstrates the effect of a 20% uplift of the 2010 GHR. I stress again that I do not purport to revise the GHR, as this court has no power to do so; instead this is a practical attempt to assist Costs Officers and avoid unnecessary delay (caused by individual re-calculation) in a busy department conducting over 8000 COP assessments per annum.

Master Whalan indicated that

This approach can be adopted immediately and is applicable to all outstanding bills, regardless of whether the period is to 2018, 2019, 2020 or subsequently. It goes without saying that this approach is subject ultimately to the recommendations of Mr Justice Stewart and his Hourly Rates Working Group and the Civil Justice Council. Ultimately the recommendations of the Working Group must be adopted in preference to my findings.

Subsequent to the decision, the Senior Costs Judge issued a Practice Note explaining some of the practical consequences.

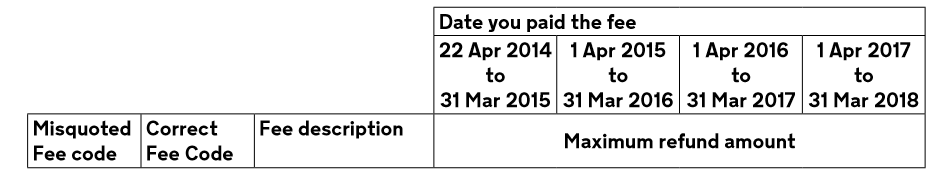

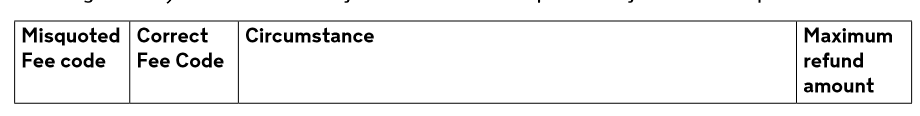

In addition, if you paid a hearing fee between 1 April 2017 and 31 March 2018, you may also be eligible for a refund.

In addition, if you paid a hearing fee between 1 April 2017 and 31 March 2018, you may also be eligible for a refund.

For more details, see

For more details, see