In Re D (A young man) [2019] EWCOP 1, Mostyn J had to consider a question that had previously been the subject of only very limited judicial consideration, namely the test for permission under s.50 MCA 2005. The case concerned a young man, D, aged 20, with autism. He had been looked after by his father and his stepmother, C, since the age of 3.

D’s mother, who was subject to a civil restraint order, applied for permission to make a substantive application concerning the nature and quantum of her contact with D. Mostyn J granted her leave under the terms of the civil restraint order to make the application for permission to make the application itself.

Under the terms of ss.50(1) and (2) MCA 2005, the mother needed permission to make a substantive application as she did not fall into one of the categories where permission is not required set out in section 50(1). Section 50(3) provides:

In deciding whether to grant permission the court must, in particular, have regard to –

(a) the applicant’s connection with the person to whom the application relates,

(b) the reasons for the application,

(c) the benefit to the person to whom the application relates of a proposed order or directions, and

(d) whether the benefit can be achieved in any other way.

Mostyn J noted that:

4. A permission requirement is a not uncommon feature of our legal procedure. For example, permission is needed to make an application for judicial review. Permission is needed to mount an appeal. Permission is needed to make a claim under Part III of the Matrimonial and Family Proceedings Act 1984. In the field of judicial review, the permission requirement is not merely there to weed out applications which are abusive or nonsensical: to gain permission the claimant has to demonstrate a good arguable case. Permission to appeal will only be granted where the court is satisfied that the appellant has shown a real prospect of success or some other good reason why an appeal should be heard. Under Part III of the 1984 Act permission will only be granted if the applicant demonstrates solid grounds for making the substantive application: see Agbaje v Akinnoye-Agbaje [2010] UKSC 13 at [33] per Lord Collins. This is said to set the threshold higher than the judicial review threshold of a good arguable case.

5. There is no authority under section 50 giving guidance as to what the threshold is in proceedings under the 2005 Act. In my judgment the appropriate threshold is the same as that applicable in the field of judicial review. The applicant must demonstrate that there is a good arguable case for her to be allowed to apply for review of the present contact arrangements.

The case had had a very lengthy and unhappy history, contact arrangements between D (at that stage a child) and his mother having been fixed some seven years previously. Having rehearsed the history, the possible scope of proceedings before the Court of Protection and (in his view) the irrelevance of the fact that D had turned 18, Mostyn J held that he applied:

13. […] the same standards to this application as I would if I were hearing an oral inter partes application for permission to seek judicial review. I cannot say that I am satisfied that the mother has shown a good arguable case that a substantive application would succeed if permission were granted. Fundamentally, I am not satisfied that circumstances have changed to any material extent since the contact regime was fixed seven years ago and confirmed by me two years ago. I cannot discern any material benefit that would accrue to D if this permission application were granted. On the contrary, I can see the potential for much stress and unhappiness not only for D but also for his family members if the application were to be allowed to proceed.

Mostyn J therefore refused the mother’s application for permission.

Comment

Being pedantic, Mostyn J was not correct to say that there was no authority on s.50. In 2010, Macur J had in NK v v VW [2012] COPLR 105 had refused permission on the basis that she considered that “section 50(3) and the associated Rules require the Court to prevent not only the frivolous and abusive applications but those which have no realistic prospect of success or bear any sense of proportional response to the problem that is envisaged by NK in this case.” Fortunately, not least for procedural enthusiasts, that approach is consistent with the more detailed analysis now given by Mostyn J.

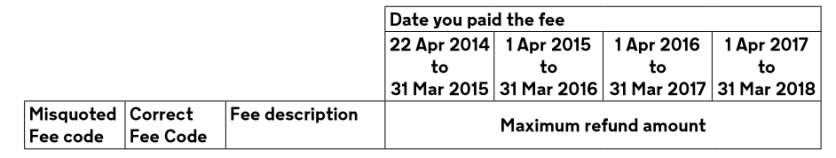

In addition, if you paid a hearing fee between 1 April 2017 and 31 March 2018, you may also be eligible for a refund.

In addition, if you paid a hearing fee between 1 April 2017 and 31 March 2018, you may also be eligible for a refund.

For more details, see

For more details, see