In Re PQ (Court Authorised DOL: Representation during Review Period) [2024] EWCOP 41, a local authority argued unsuccessfully that Article 5 did not require a rule 1.2 representative to be appointed during the review period, when the court had made best interests decisions for PQ and authorised care arrangements giving rise to a deprivation of liberty, which was to be reviewed in 12 months. The court (perhaps unsurprisingly) rejected this submission having regard to the clear findings of Charles J in Re NRA [2015] EWCOP 59 and Re JM [2016] EWCOP 15, and given PQ’s specific circumstances. The court did not however rule out the possibility that “in some cases” compliance with Article 5(4) may not require the appointment of a litigation friend or representative.

Had there been an available rule 1.2 representative PQ could have been discharged as a party. However, in this case, no rule 1.2 representative was available.

The judge was aware that legal aid funding depended on an oral hearing being listed or likely to be listed[1], but was not willing to list what could be an unnecessary hearing as a device to secure legal aid. The judge refused to discharge the Official Solicitor as litigation friend and directed her to provide the level of representation to fulfil a role similar to an RPR or rule 1.2 representative. The judge was aware from an email from a Legal Aid Agency (LAA) Caseworker that legal aid funding would not normally keep a certificate open during a review period. In the event that funding was withdrawn, there would be a further hearing and the following directions would apply:

- A full explanation from the LAA of the decision not to fund representation;

- The LAA would be requested to secure ongoing funding pending determination by the court of PQ’s representation;

- The local authority was to review its decision not to fund a rule 1.2 representative and provide a written explanation if it decided not to fund.

- The Secretary of State for Justice would be joined as a party and required to provide evidence as to the provision of funds for a professional 1.2 representative.

The judge directed that the judgment is provided to the Legal Aid Agency and Secretary of State for Justice with a request they consider the implications.

Comment:

- Whilst Poole J did not rule out that representation (either a litigation friend or rule 1.2 representative) might not always be required to comply with Article 5(4), it should be borne in mind that Charles J heard detailed argument over the issue in Re NRA, Re JM and later Re KT [2018 EWCOP 1] from several local authorities, and the Secretaries of State for Health and for Justice who were joined as parties[2]. He reached clear and reasoned view that the minimum procedural requirements of Article 5 and the common law requires “some assistance from someone on the ground who considers the care package through P’s eyes and so provides the independent evidence to the COP that a family member or friend can provide”.

- Sadly this case reminds readers of the perverse incentives that continue to permeate funding decisions in this area of law. As Poole J pointed out, in the end the states pays, and the solution he felt compelled to adopt means the state is likely to pay more than it should do.

[1] Regulation 52, Civil Legal Aid (Merits) regulations 2013, although this does not appear to have been cited to the judge

[2] Poole J describes Charles J’s efforts to find a practical solution as “Herculean”- see paragraph 32.

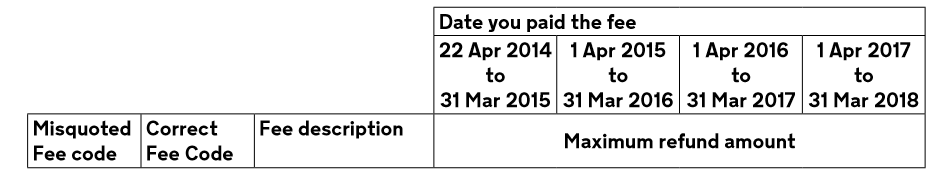

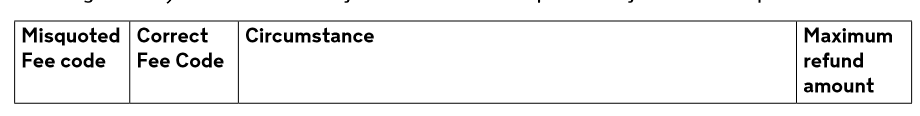

In addition, if you paid a hearing fee between 1 April 2017 and 31 March 2018, you may also be eligible for a refund.

In addition, if you paid a hearing fee between 1 April 2017 and 31 March 2018, you may also be eligible for a refund.

For more details, see

For more details, see